Five years ago, a senior executive painted me a nautical picture of her large, established organization’s goal for digital transformation: to operate not like an unwieldly tanker but as a flotilla of sailboats. Via the collective actions of small cross-functional teams, the organization would sense and seize opportunities to continuously transform—just like the nimble start-ups in its exceedingly competitive industry.

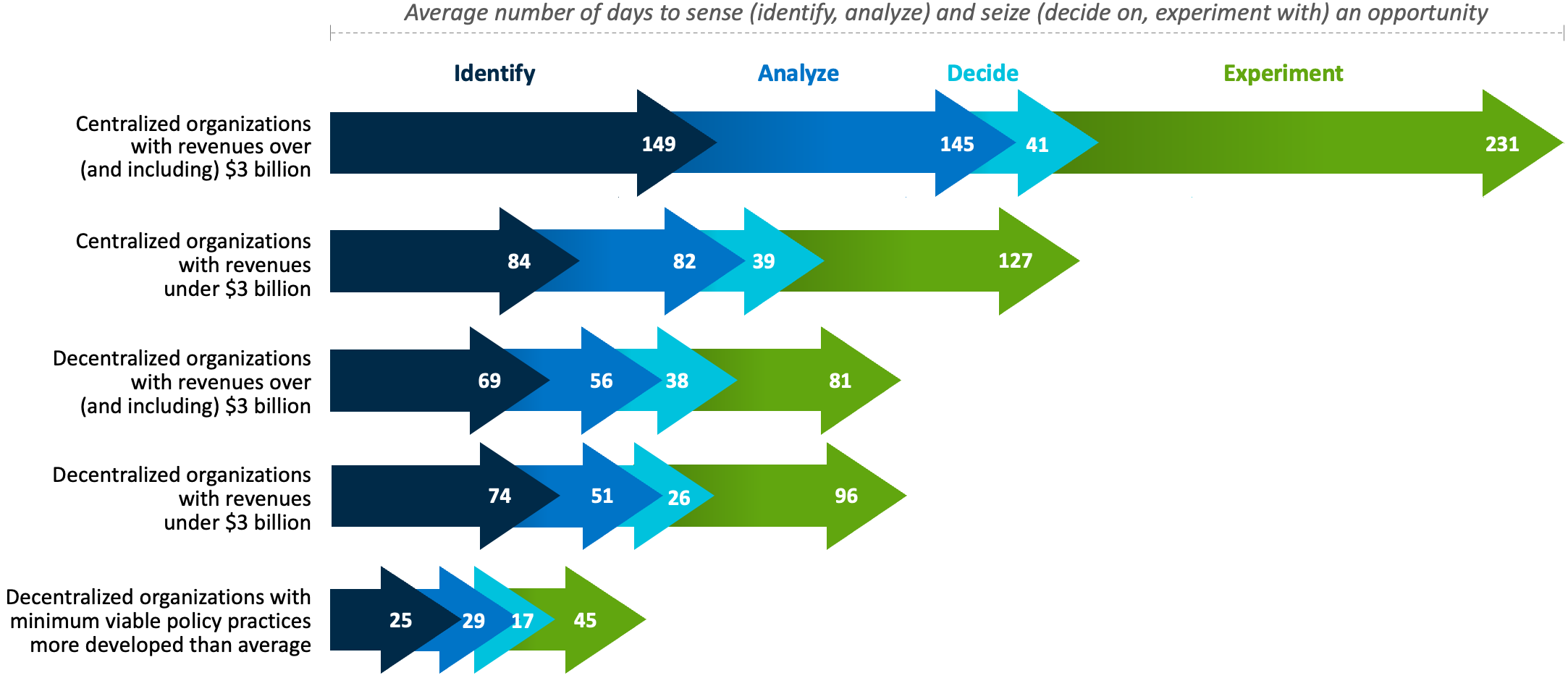

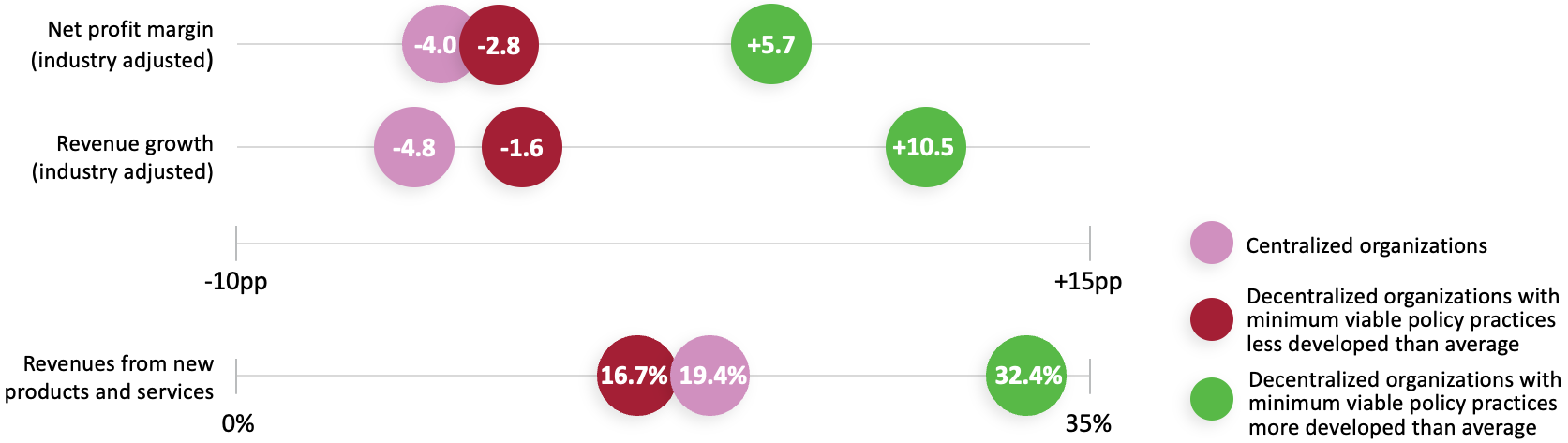

Data from a recent MIT CISR survey[foot]This research briefing is based on data from the MIT CISR 2022 Decision Rights for the Digital Era Survey. Respondents (N=342) comprised organizational leaders representing 61 organizations with annual revenues of at least US$3 billion and 272 organizations with annual revenues under US$3 billion. Fifty-seven percent of the organizations represented in the survey operated outside of North America.[/foot] confirmed that it is indeed possible for large, established organizations to operate in an equally agile fashion as their smaller industry peers, particularly if the organizations decentralize their decision-making. To realize this dynamic capability,[foot]Dynamic capabilities represent the ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments, as described in S. L. Woerner, L. Owens, and C. M. Beath, “Build Eight Dynamic Capabilities for Digital Business Model Change,” MIT CISR Research Briefing, Vol. XXI, No. 8, August 2021, https://cisr-mit-edu.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/publication/2021_0801_DynamicCapabilities_WoernerOwensBeath.[/foot] leaders retain strategic decision rights (the authority and accountability for what the organization needs to achieve and why) but distribute operational decision rights (the authority and accountability for how to best achieve strategic goals) to teams that are closest to customers, offerings, technology, and processes. This approach, also referred to as creating autonomous, empowered, or self-managing teams, focuses on teams realizing outcomes—as opposed to leaders dictating processes and required output—through the iterative realization of solutions that are desirable, feasible, and viable.[foot]For a case example illustrating attributes of desirability, feasibility, and viability, see N. O. Fonstad, “Innovating Greater Value Faster by Taking Time to Learn,” MIT CISR Research Briefing, Vol. XX, No. 2, February 2020, https://cisr-mit-edu.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/publication/2020_0201_InnovatingGreaterValueFaster_Fonstad. [/foot]

Today, the aforementioned organization has made great strides in decentralizing decision-making in its digital and IT teams, but leaders in other parts of the enterprise are slow to give up their operational decision rights. Our recent survey showed this is a common struggle: the leaders in our survey reported that on average 47 percent of the teams in their organization (or the part of the organization they were most familiar with) could make decentralized decisions.[foot]The decentralized decision-making questions in the survey asked about the extent to which (and what percentage of) teams were enabled to make decisions without a manager’s oversight, decide for themselves how to best solve customer- or business-focused problems, revise their solutions when conditions change, and define their own performance targets and commitments.[/foot] Yet our survey data showed that granting operational decision rights to only a select few business units or corporate functions hindered an organization’s ability to sense (i.e., identify and analyze) and seize (i.e., decide on and experiment with) opportunities, thereby limiting its innovative capacity and financial performance. This research briefing describes the extent to which decentralized decision-making can help large, established organizations achieve greater organizational agility, and which practices help to turn size into an advantage for improving organizational performance.